By: Kenneth Appiah Bani

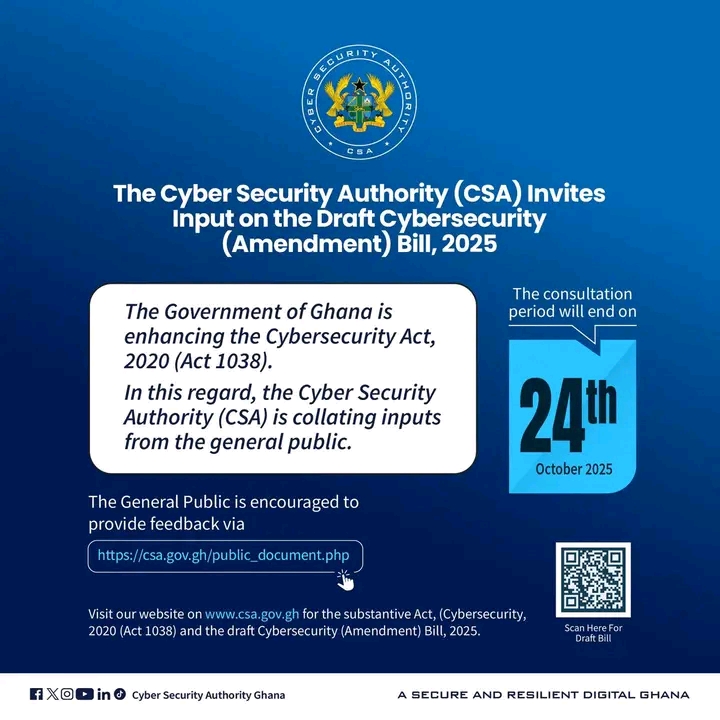

Ghana’s Cyber Security Authority (CSA) has moved to tighten the country’s cyber laws through a sweeping amendment to the Cybersecurity Act, 2020 (Act 1038). The proposed Cybersecurity (Amendment) Bill, 2025 was developed and refined via a CSA-led public consultation that concluded on October 24, 2025.The consultation invited input from all quarters cybersecurity professionals, service providers, civil society groups and the general public to ensure the law reflects stakeholders’ views. In announcing the review, the government emphasized that the updated law “confers powers on the Cyber Security Authority to investigate and prosecute cybercrime on the authority of the Attorney-General and recover proceeds of cybercrime; revise the object and functions of the Cyber Security Authority; revise the governance and administration of the Cyber Security Authority; revise the enforcement powers of the Cyber Security Authority and provide for related matters”. In other words, the amendments are designed to expand the CSA’s mandate, strengthen enforcement, and address emerging threats.

The amended Act’s stated objectives, as re-worded in the Bill, underline these changes. For example, the Bill explicitly adds to the Authority’s objects the prevention and detection of cybercrime and the “confiscation of proceeds of cybercrime”. It also retains broad goals such as regulating cybersecurity activities, protecting critical infrastructure, promoting a secure digital ecosystem, raising public awareness, and collaborating internationally. Notably, the amendments reflect a new focus on research, threat intelligence and incident response. Although the Bill does not detail “cyber threat intelligence” in the section 3 objects, its long title and provisions clearly signal that the CSA should now spearhead threat analysis and investigations. As one observer noted, the “32-page document seeks to update the 2020 Cybersecurity Act, addressing emerging threats like artificial intelligence-driven scams, blockchain vulnerabilities, and harassment campaigns”.In short, the amendment package is framed as essential to “shield critical infrastructure from banks to power grids against attacks that cost the country millions in losses” (as Ghana lost over GH¢23.3 million to cybercrime in 2024 alone).

The Amendment Bill dramatically expands the powers of the Cyber Security Authority. A new Section 4A adds numerous functions beyond the original law. For instance, subject to Article 88 of the Constitution, the CSA can now investigate and with the Attorney-General’s approval prosecute cybercrime under the Act. This is a significant change: it makes the CSA an active law-enforcement agency rather than merely a regulator. Section 4A also tasks the CSA with establishing standards and certifying the security of emerging technologies (artificial intelligence, cloud services, quantum computing, big data analytics, IoT and blockchain), and with accrediting “cybersecurity establishments” ranging from critical-infrastructure operators to nonprofit cyber institutes. Subsection (f) of 4A even directs the CSA to “promote the online protection of women, elderly, persons with disabilities and underserved populations” and to safeguard digital rights generally (4A(h)). Thus the CSA’s remit is broadened to cover cybersecurity awareness and civil society engagement as well as technical standards.

The Bill explicitly endows CSA officers with police-like powers. Newly inserted Section 20B provides that the Director-General, Deputy Director-General and designated officers of the CSA “shall exercise the powers of a police officer, including powers of arrest, search and seizure” and enjoy the same rights and immunities under Ghana’s Police and Criminal Procedure Acts. In effect, CSA investigators can enter premises, seize evidence and make arrests in cybercrime cases. In practice, the CSA has already demonstrated a more active law-enforcement role: its Cyber Crime Unit frequently collaborates with the CID on investigations.Under the new law, this will be formalized. For example, Section 59B (inserted after Section 59A) explicitly requires the CSA “upon the occurrence of a cybersecurity incident or a cybercrime” to conduct criminal investigations and prosecute the offence.It even extends the CSA’s jurisdiction to prosecute all offences under Ghana’s Electronic Transactions Act (2008). Furthermore, 59B(3) gives the CSA statutory power to apply to court for confiscation orders against the proceeds and assets of cybercrime offenders. Together, these provisions make the CSA a full-fledged investigator and prosecutor of cyber offences, rather than merely an advisory regulator.

The expanded powers come with new enforcement tools. The Bill creates a suite of information-gathering and evidence-collection powers (Sections 59A–59K). For example, Section 59A makes it a criminal offence (punishable by up to 5 years’ jail or ₵20,000 in penalty units) to knowingly violate the Act or its regulations, or to obstruct CSA officers in the performance of their duties. Section 59C empowers the CSA to issue written notices compelling attendance and the production of information relevant to an investigation. If a person claims legal privilege or secrecy over the information, the CSA can apply to the High Court for a production order. Under Section 59D, a CSA investigative officer may apply ex-parte to the High Court for a production order requiring any person “in possession or control of a computer or computer system” to submit specified data from that system. Section 59E sets strict safeguards: a court may grant such an order only if the officer has shown the data sought is commensurate, necessary and proportionate for a specific investigation, and if privacy of uninvolved third parties will be maintained.

Similarly, Section 59F authorizes ex-parte warrants to access, search and seize computer data or systems. A warrant may allow law enforcement to copy or image data, or even search other computers connected to the target network if reasonable grounds exist. Section 59G requires that any such warrant be strictly proportionate and accompanied by protective measures for privacy. The Bill also introduces provisions for data preservation: Section 59H mandates that internet or electronic communications providers preserve records on written request by law enforcement, pending a court order. An officer can then apply ex-parte for a preservation order, which must be limited to data “particularly vulnerable to loss or modification”. Under Section 59I, a High Court may grant the order if the officer complied with the notice requirement and shows the order is needed to avoid frustrating the investigation; preservation orders last 90 days (renewable) and must be kept confidential.

In addition, the CSA can conduct inspections and audits. Section 59J allows the CSA to appoint inspectors who may, with a warrant, enter and inspect premises or audit computer systems. Even without a warrant, an inspector may inspect premises if they believe it is “necessary to ensure compliance” by a CII owner or service provider, provided seven days’ written notice is given. Inspectors must identify themselves and may examine documents, equipment or require persons on site to provide relevant information. All these new investigative powers come with built‑in privacy protections (e.g. requiring privacy measures in any disclosure order) and with criminal penalties for abuse. Moreover, Section 59K enshrines witness protection: it guarantees that any person who reports cybercrimes (or related regulatory infractions) can remain anonymous unless they explicitly consent, and that their identity and statements are confidential and privileged. The CSA is further required to take “all necessary and reasonable steps” to protect the safety of witnesses or informants and their families. In sum, the amendments give the CSA sweeping enforcement and investigative reach, backed by strict rules on judicial oversight and witness confidentiality.

The Amendment Bill creates several new offences and significantly increases penalties to deter cybercrimes. In the criminal sections, the heading of what was once “Other Online Sexual Offences” (Section 67) is changed to “Other Cybercrime”, reflecting a broader scope. Subsection 67(2) is redrafted to set a minimum sentence of 3 years for any offence under Section 67. The Bill also adds two entirely new sections: Section 67A defines and criminalizes a wide range of cyberbullying and online harassment behaviors. Under 67A, it is an offence for anyone to use the internet or electronic media to bully a child or adult for example, sending threatening or lewd messages, making sexual advances to a child, or repeatedly contacting someone in an unwelcome way. It also criminalizes creating fake online identities to follow or harass others, and using online services or devices to track or monitor children (or other persons) without consent. Outright spamming, obscene or threatening communications are likewise prohibited. Conviction under Section 67A carries a fine (2,500–5,000 penalty units) or 1–3 years’ imprisonment, or both. These provisions explicitly target forms of online harassment that have become common, but critics warn they are drafted broadly and could capture legitimate speech (for example, satire or journalism) if not carefully applied.

Section 67B creates a new offence of cyberstalking. It makes it illegal to use internet platforms (social media, chat rooms, online games or even “augmented reality” apps) to stalk, harass or disseminate false information about a person. The law even bans assuming a false online identity for these purposes. A conviction under 67B carries up to 10 years’ imprisonment or a fine (up to 10,000 penalty units). In effect, the bill recognizes stalking in cyberspace as a serious offence on par with other violent crimes.

The amendments also introduce new computer-specific crimes. After Section 94, two new sections (95A and 95B) add “computer-related forgery” and “computer-related fraud” as offences. Section 95A targets tampering with digital data: it forbids anyone from “inputting, altering, deleting or suppressing” computer data so as to create inauthentic legal documents or records,“regardless of whether or not the data are directly readable”.Anyone convicted under 95A is deemed to have committed forgery under Ghana’s Criminal Offences Act, and faces the same punishment as for traditional forgery.Section 95B similarly outlaws digital fraud schemes: it makes it an offence, with fraud intent, to cause loss of property by manipulating computer data or functions or by using deceptive false information via a computer.A violator is deemed to have committed false pretence fraud under Section 131 of the Criminal Offences Act and is punished accordingly. These provisions align Ghana’s law more closely with international standards by covering crimes that involve cyber techniques but effect traditional harms (fraud, forgery).

In addition, several existing penalty clauses are revised upward.For example, unauthorized access and data interception (Section 94) now carries a minimum fine of 2,500 units and up to 15,000, or 2–5 years’ jail. Notably, any attempt to access critical information infrastructure (CII) or its dependencies even if unsuccessful is explicitly criminalized, as is the tampering or destruction of CII components. The fine range for breaching prohibitions on critical infrastructure is set at 4,000–25,000 units. The licensing regime is also tightened: operating a paid cybersecurity service without a CSA licence is made an offence, and providing any service on a non-profit basis without accreditation is similarly banned, subject to very large administrative fines (₵50,000–₵100,000 in penalty units). Even failure to comply with CSA directives or incident-reporting rules can trigger penalties under the new enforcement power clauses.Overall, the amendments dramatically stiffen sanctions reflecting CSA data that fraud and impersonation already account for over 94% of cybercrime losses and that incidents have surged (from 1,317 reported cases in H1 2024 to 2,008 in H1 2025).

The Bill significantly deepens the regime for Critical Information Infrastructure (CII). Under the amendment, the Minister (on CSA advice) can designate any computer system or network as CII if its compromise would seriously affect national security, the economy, health, or public safety. The criteria are broad and detailed: they explicitly include communications networks, banking systems, utilities, transportation, emergency systems, government services, and indeed any “digital services” or “supply chain” deemed critical. Once designated, CII owners must register with the CSA under new Section 36, providing details (including a designated point of contact) and paying annual fees set by the Authority. The CSA will issue a Certificate of Registration to each CII. Failure to register or notify the CSA of ownership changes now attracts administrative penalties.The Minister also gains authority to de-designate infrastructure if it no longer meets the criteria, ensuring the CII list can adapt.

The Bill envisions a more proactive incident response framework. Section 47 is amended to require every Sectoral Computer Emergency Response Team (Sectoral CERT) to report any incident affecting a designated CII, licensed service provider or other “relevant person” to the National CERT within 24 hours. The State has already established multiple Sectoral CERTs (for finance, energy, etc.), and this clause enforces coordination: non-compliant Sectoral CERTs face financial penalties under the Fund. In addition, Section 83 (on mutual assistance) is updated to include provisions for emergency disclosure: the law now explicitly allows a service provider to be ordered to rapidly disclose specified data in an emergency even without a mutual legal assistance treaty, subject to definitions of “emergency” (a situation posing imminent risk to life or safety). These measures show an intent to ensure quick action on critical incidents.

The amendments introduce a more structured licensing and accreditation regime for cybersecurity roles and services.Section 49 is tightened: it now plainly forbids anyone from offering a paid cybersecurity service without a CSA licence. Likewise, no one may offer (even on a non-profit basis) such services without CSA accreditation.Violators must pay an administrative penalty up to 100,000 units (an extremely high sum) or the equivalent cost of any damage and illicit gain.In effect, the Bill centralizes regulation of the cyber profession.

In turn, Section 57 is completely replaced with a new accreditation framework for cybersecurity professionals and practitioners. The Authority must establish an accreditation process.Individuals may not practise as cybersecurity professionals/practitioners unless accredited, and organizations may not knowingly hire or engage unaccredited persons.Infractions of these rules carry penalties (₵250–₵20,000 in units).These changes essentially require certification of all cyber consultants and experts, which supporters say will ensure quality and ethics in the field, though some worry it could create barriers for small providers.

Parallel to accreditation, the Bill establishes a “cyber hygiene certification” scheme (Sections 57B–57C).The CSA must set up a program to certify cybersecurity firms and professionals in accordance with international best-practice standards. Accredited certifiers will charge a fee for cyber-hygiene audits (at rates set by the CSA), with a portion of revenue (30%) channeled into the national cybersecurity fund.Overcharging beyond the approved flat rate incurs fines.This initiative is meant to raise minimum security standards across the economy.Also, new Sections 58A–58B instruct the CSA to create mechanisms for certifying the security of cutting-edge technologies and for accrediting cybersecurity research/NGO institutions, further professionalizing the ecosystem.To support all this, Section 59(1) adds a clause explicitly listing “certification of the security of innovative and emerging technologies including Artificial Intelligence, cloud, quantum, big data, and blockchain” as among the CSA’s powers.

The Bill makes a number of governance tweaks.The CSA Board’s composition is expanded: the Ministers of Foreign Affairs and of Gender, Children and Social Protection are now ex-officio members.Section 13 is amended to add representatives of national security agencies (Intelligence Bureau, National Communications Security Bureau) to the Joint Cybersecurity Committee, as well as a designated Data Protection Commission nominee.Subsections are added to ensure that members who miss meetings can be replaced, and that any new appointment fills only the unexpired term.

The role of the Joint Cybersecurity Committee (JCC) is also clarified and deepened.Under the new Section 14, the JCC must work closely with the CSA and sector regulators to identify cyber-risks, develop aligned policies, coordinate responses across sectors, and facilitate secure information-sharing.The JCC is now explicitly tasked with collaborating “to tackle cybercrime” and to use its platform for incident sharing and response.These provisions aim to foster better government–private coordination.

The internal structure of the CSA is strengthened.A new Section 15A allows the President to appoint Deputy Director-Generals as needed, who can act on behalf of the DG and oversee specialized portfolios.Employee terms are enhanced by Section 20A: CSA staff must be given pay and benefits no less favorable than those of Ghana’s security and intelligence agencies.Together with the expanded powers and funding (below), this is intended to make the CSA an elite security agency.

On funding, Section 31 is amended to increase the CSA Fund’s revenue sources.Notably, 50% of all fines under the Act will now go to the Fund, and the Fund will receive specified shares of the national communications service tax (12%) and corporate tax (9%) each year.Government service fees and voluntary contributions remain in the list.In effect, the CSA’s budget is significantly beefed up, reflecting the broader role it is being given.

Finally, Section 90 is tweaked to grant Circuit Courts jurisdiction over a wider range of cyber offences (Sections 62–68A), making prosecution more accessible.The definition section (Section 97) is overhauled to insert modern terms: “Artificial Intelligence”, “block-chain based technology”, “big data”, “cloud technology”, “Internet of Things (IoT)” and even “digital services” are defined for the first time.New definitions of “emergency” and “freezing” align Ghana’s law with international norms on law enforcement emergencies and asset freezes.These updates ensure there is no ambiguity about the law’s scope in cutting-edge areas.

The government and many experts portray the amendments as urgently needed in the face of rising threats. CSA Director-General Divine Selase Agbeti has warned that data from dozens of Ghanaian institutions including ministries, banks, hospitals and universities has been found on the dark web, highlighting the scale of the problem. He and other officials note that with internet penetration now over 70% of the population, cyber risks have grown rapidly, costing the economy millions (GH¢23.3 million in 2024).They argue that the CSA’s new investigative powers and resources will help close enforcement gaps.Minister Samuel Nartey George stressed that “cybersecurity must now be treated with the same seriousness as physical safety” and vowed intensified crackdowns on cyber criminals.Prof. Elsie Effah Kaufmann of the University of Ghana praised the emphasis on research and capacity-building, noting that cyberspace “is not inherently safe” and must be managed intelligently.

However, civil society and legal experts have sounded cautionary notes about the breadth of the new law.A recent analysis in the Labari Journal observed that the draft amendments “grant sweeping powers to regulators and law enforcement, with scant checks on potential abuses”.For example, inspectors may be able to conduct warrantless audits simply by giving short notice, and investigators can seize data and freeze assets (up to 180 days, under the draft) without advance public scrutiny. Broad new offences like those in Sections 67A–67B raise concerns: critics warn that their vague wording (e.g. outlawing “unwanted contact” or “false information”) could ensnare legitimate speech and activism.The Labari piece cautioned that, without strict judicial oversight, these provisions risk transforming cybersecurity laws into tools of surveillance rather than protection.

Human-rights advocates also point to the need for safeguards.Although the amendment includes privacy conditions on data orders (requiring protection of third-party data) and witness anonymity, civil liberties groups may push for even stronger oversight mechanisms such as periodic legislative reviews or an independent privacy commissioner especially given the Act’s new powers to intercept and inspect digital communications.Importantly, the consultation process itself reflects some balancing: the consultation form and CSA statements stress transparency and encourage written submissions.The final shape of the Bill may yet be influenced by feedback, as observers expect revisions (for example, making some intrusive powers subject to warrants or clarifying offence definitions) before it is presented to Parliament.

On the other hand, many in the tech community support the overhaul. They argue that Ghana’s cybersecurity law had lagged behind technological change and that stronger deterrence is needed.The fact that fraud and cyber-enabled theft already account for the vast majority of cybercrime losses is often cited as justification for tougher penalties.Likewise, businesses managing critical infrastructure (power, finance, telecoms) have generally welcomed clearer rules and standards, even if compliance imposes costs.The addition of licenses, accreditation, and national certification standards is seen by some industry groups as a positive step toward professionalizing the sector and attracting foreign investment (by aligning Ghana with global norms).The CSA’s board-level inclusion of data protection and foreign affairs experts (new Section 13 members) is also viewed as a signal that privacy and international cooperation will factor into enforcement.

In conclusion the Ghana’s Cybersecurity (Amendment) Bill, 2025 represents a comprehensive modernization of the country’s cybercrime framework.By expanding the CSA’s mandate, beefing up enforcement powers, and sharpening the law’s focus on new technologies and threats, the government aims to stem the rising tide of cyber fraud, ransomware and online abuse.The amendments would allow faster incident response, more robust criminal prosecutions, and greater protection for vulnerable users.At the same time, they raise important questions about the balance between security and freedom in the digital domain.The final outcome will depend on how Parliament negotiates these trade-offs; for now, Ghana has signaled its intention to treat cyber threats with urgency comparable to that accorded physical crime.

Sources: The analysis above is based on the official Cybersecurity (Amendment) Bill, 2025 (as released by the CSA) and related news reports from Ghanaian media, which detail the changes, objectives and commentary on the draft law.