By: Kenneth Appiah Bani

The recent announcement that music producer MOG Beatz has won his copyright infringement case against dancehall artist Shatta Wale marks a defining moment in Ghana’s creative industry. It is a moment that goes beyond two individuals and speaks to the long-standing challenges surrounding intellectual property rights in our music space. For years, I have been a staunch advocate for stronger IP frameworks in Ghana, and this ruling, while not entirely surprising, highlights the very issues I have consistently raised: the lack of proper structures, the absence of standard practices, and the vulnerability of creators in an industry that too often overlooks the importance of legal ownership.

For those who have followed Ghana’s entertainment ecosystem closely, the conflict between MOG Beatz and Shatta Wale was always a matter waiting to explode. Our institutions tasked with safeguarding intellectual property simply have not lived up to their mandate. Education around IP is minimal, enforcement is almost non-existent, and many creatives operate without a clear understanding of their rights. Because of this systemic neglect, disputes over credits, royalties, and ownership continue to surface with alarming frequency.

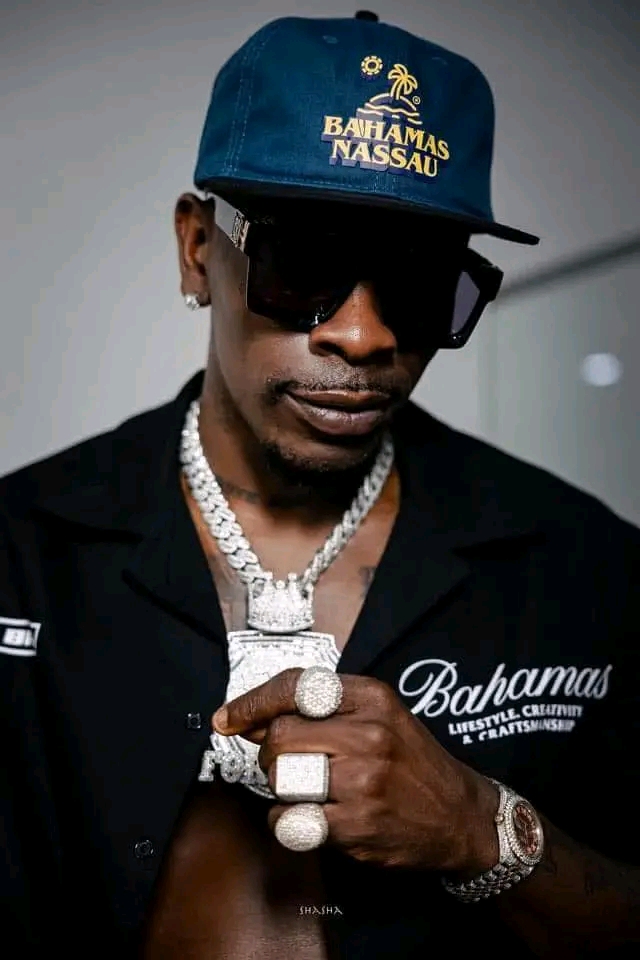

MOG accused Shatta Wale of taking production credit for works he did not produce, allegedly in an attempt to improve the value of Shatta’s music catalog. These were no ordinary accusations. In a country where Shatta Wale commands massive influence, calling out such an act was bold and risky. But the truth in IP matters does not lie in popularity, wealth, or fan base it lies in documentation, contribution, and the law. MOG’s claims, now vindicated, raise important questions about how songs are created, who owns what, and what agreements if any govern those collaborations.

To understand why this case mattered, one must appreciate how music ownership works. When a song is created, there are two key components: the composition and the lyrics. The producer typically owns the composition, especially when they create the beat independently and later send it to the artist. The artist then adds lyrics, creating a joint ownership situation unless a formal agreement states otherwise. In modern global practice, such collaborations usually result in shared publishing rights, with a 50/50 split being the standard when the producer provides a pre-made beat. Beyond composition lies the master recording the final song. Ownership of the master depends on who finances the recording. But even here, ambiguity often exists, especially when no agreed payment or contract is signed. In such cases, the producer may unintentionally become the financier by virtue of contributing the studio, equipment, or time, thereby gaining a claim to the master.

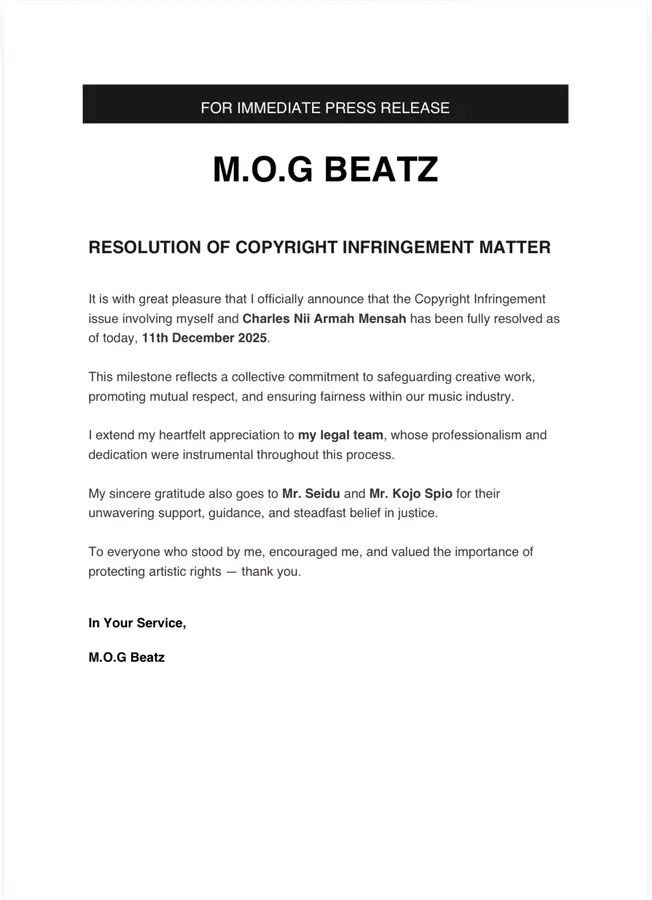

These foundational rules of music IP underscore why the ruling in MOG’s favour is so significant. It demonstrates that the courts recognize producers’ rights and will enforce them when necessary. According to widely circulated reports, Shatta Wale has been ordered to pay $20,000 to MOG an amount many observers on social media have downplayed or exaggerated in equal measure. But the true value of this ruling is not in the money awarded; it lies in the precedent it sets. MOG’s official press release confirms that the matter has been resolved, and the tone of his statement reflects professionalism, gratitude, and relief. It speaks to a journey that required courage and a commitment to the principle that artistic work must be protected, not exploited.

The reaction from the public has been intense. Some view this as a symbolic defeat for Shatta Wale, especially in light of his earlier claims that he had once considered gifting MOG a G-Wagon and a mansion. Others see it as a triumph for producers across Ghana who have long felt marginalized and undervalued. Regardless of personal loyalties, it is hard to deny that this ruling exposes the troubling dynamic within the Ghanaian music industry: producers often work without contracts, artists sometimes take unchecked liberties, and catalog sales or licensing deals proceed without proper consultation with the rightful owners of the composition.

What makes this case especially relevant is its potential impact. It forces both artists and producers to rethink how they operate. It underscores the importance of split sheets, written agreements, proper registration of works with copyright offices and collection management organizations, and transparency in catalog management. It reminds artists that verbal agreements and promises are not legally binding. It teaches producers that accepting quick cash or favours without documentation can cost them their rights. It challenges institutions to do more, to educate creatives, and to enforce the systems that already exist in law but rarely in practice.

This ruling also has broader implications for Ghana’s international reputation. As the global music market becomes more connected, Ghanaian artists and producers increasingly collaborate with international stakeholders. In such an environment, respect for intellectual property is not optional. It is the standard. This case sends a message that Ghana’s creative industry is ready to align with global best practices and that those who attempt to cut corners will face consequences.

Ultimately, the MOG Beatz–Shatta Wale case is more than a legal battle; it is a reflection of a young creative industry grappling with maturity. It is a reminder that passion alone cannot sustain a career professionalism, knowledge, and legal awareness must accompany it. It is a wake-up call for artists, producers, managers, and institutions alike. Most importantly, it is a victory for every Ghanaian creator who has ever felt powerless, uncredited, or sidelined.

MOG Beatz did not just win a copyright case; he won a moment of reckoning for the industry. He affirmed that creative work deserves respect, that the law can protect those who dare to stand up, and that Ghana’s music industry must evolve if it wants to thrive. And for those of us who have long advocated for stronger IP rights in this country, this moment this ruling is proof that the fight is not in vain.