By: Kenneth Appiah Bani

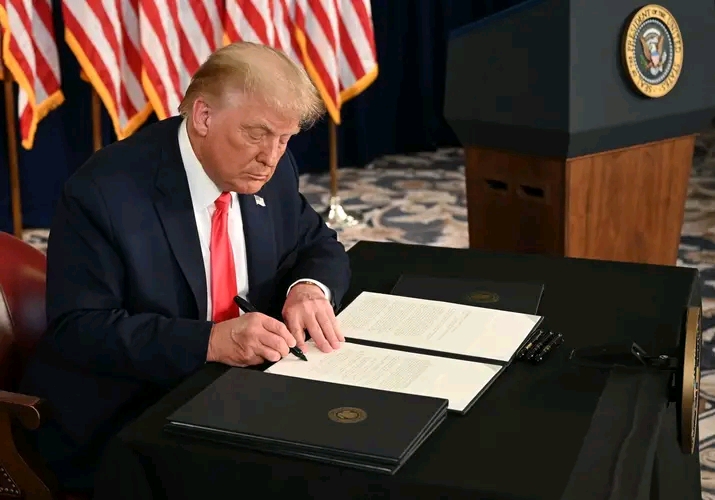

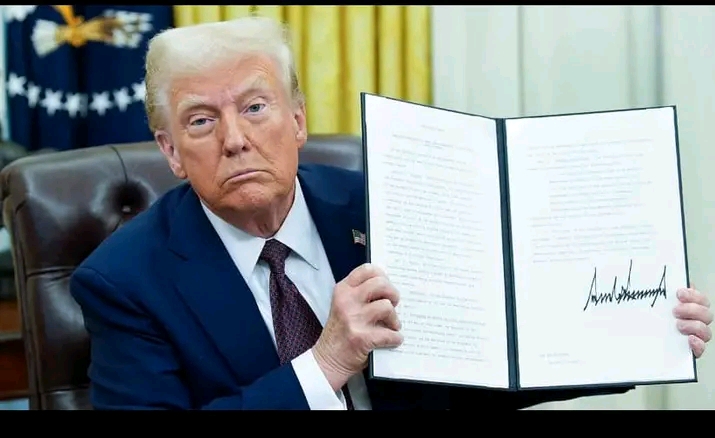

On January 20, 2025, the President of the United States signed an executive order aimed at reshaping the interpretation of birthright citizenship in the country. Titled “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship,” the order seeks to clarify and enforce limitations on who qualifies for automatic

U.S. citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment was introduced during the Reconstruction era to secure the rights of newly freed slaves, but its interpretation has been expanded over time to include individuals born in the United States to non-citizen parents.

The order emphasizes the profound privilege of U.S. citizenship while addressing historical and legal contexts. The Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees citizenship to those born or naturalized in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction, serves as the cornerstone of this policy. However, the language amendment has long been debated, particularly regarding the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”

The order specifies that birthright citizenship does not automatically extend to individuals born in the United States under certain circumstances:

1. When the mother was unlawfully present in the U.S. at birth, and the father was neither a U.S. citizen nor a lawful permanent resident.

2. When the mother’s presence in the U.S. was lawful but temporary—such as on a tourist, student, or work visa—and the father did not meet the same citizenship or residency criteria.

Types of Non-Immigrant Visa

1. H-1B: Temporary worker in a specialty occupation (e.g. IT, engineering, finance).

2. H-1C: Temporary worker in a specialty occupation in the healthcare industry.

3. H-2A: Temporary worker in agricultural labor.

4. H-2B: Temporary worker in non-agricultural labor (e.g. hospitality, construction).

5. J-1: Exchange visitor (e.g., intern, trainee, teacher, researcher).

6. K-1: Fiancé(e) of a U.S. citizen.

7. L-1: Intra-company transferee (e.g. executive, manager, specialized knowledge worker).

8. O-1: Temporary worker in the sciences, arts, athletics, or entertainment.

9. P-1: Temporary worker in the arts, athletics, or entertainment (e.g. athletes, performers).

10. Q-1: Cultural exchange visitor (e.g. interns, trainees, cultural exchange participants).

11. R-1: Temporary religious worker with a nonprofit organization.

Here are some examples illustrating the diverse range of nationalities and circumstances under which non-citizen parents may give birth to U.S. citizen children.

1. Mexican Nationality: Maria, a Mexican national, gives birth to a child in the United States while on a temporary visa. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

2. Chinese Nationality: Wei, a Chinese national, gives birth to a child in the United States while working on a temporary work visa. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

3. Indian Nationality: Rahul, an Indian national, gives birth to a child in the United States while studying on a student visa. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

4. Canadian Nationality: Sophie, a Canadian national, gives birth to a child in the United States while on a temporary visa. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

5. Nigerian Nationality: Aisha, a Nigerian national, gives birth to a child in the United States while seeking asylum. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

6. Brazilian Nationality: Luana, a Brazilian national, gives birth to a child in the United States while working on a temporary work visa. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

7. Filipino Nationality: Ana, a Filipino national, gives birth to a child in the United States while on a temporary visa. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

8. Russian Nationality: Sergei, a Russian national, gives birth to a child in the United States while working on a temporary work visa. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

9. South African Nationality: Thembi, a South African national, gives birth to a child in the United States while studying on a student visa. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

10. Korean Nationality: Min-ji, a Korean national, gives birth to a child in the United States while on a temporary visa. The child is considered a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment.

Implementation and Enforcement

Federal departments, including the Departments of State, Justice, and Homeland Security, are directed to revise their policies accordingly to ensure consistency. These agencies must issue public guidance on the implementation of the order within 30 days of the order.

The policy applies only to individuals born in the United States 30 days after the order’s issuance, preserving the rights of those already recognized as citizens. Additionally, the order explicitly protects the citizenship rights of children born to lawful permanent residents.

The controversy surrounding birthright citizenship has sparked heated discussions about national identity, immigration policy, and the limits of executive power. The debate has significant implications for the future of American citizenship and the lives of thousands of individuals born in the United States to non-citizen parents.

Background

Some Americans argue that birthright citizenship is being abused by individuals who travel to the United States specifically to give birth and secure citizenship for their children, a phenomenon often referred to as “birth tourism.” President Donald Trump has been a vocal critic of birthright citizenship, arguing that it incentivizes illegal immigration.

Legal Challenges.

However, this move was met with swift legal challenges, and a lot of federal judges issued a temporary restraining order blocking its implementation. To cancel birthright citizenship, Trump would have needed to navigate a complex process involving Congress and the courts, potentially requiring a constitutional amendment.

Agencies and Organizations

Several agencies and organizations have taken President Trump to court over his executive order on birthright citizenship. These include:

● American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU): The ACLU has been a vocal opponent of Trump’s immigration policies, including his executive order on birthright citizenship. They argue that the order is unconstitutional and violates the 14th Amendment.

● National Immigrant Justice Center: This organization filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration, challenging the executive order on birthright citizenship. They argue that the order would lead to the denial of citizenship to thousands of people born in the United States.

● Pangea Legal Services: This organization filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration, challenging the executive order on birthright citizenship. They argue that the order is unconstitutional and would lead to the denial of citizenship to thousands of people born in the United States.

● Multiple States: Several states, including California, New York, and Illinois, have filed lawsuits against the Trump administration, challenging the executive order on birthright citizenship. They argue that the order is unconstitutional and would lead to the denial of citizenship to thousands of people born in the United States.

In response to the executive order, a coalition of states, the District of Columbia, and the City and County of San Francisco have filed a lawsuit against the President of the United States, federal agencies, and their officials. The complaint argues that the executive order violates the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and will have severe consequences, including:

1. Stripping children of their constitutional rights: Leaving them stateless and without access to federal benefits, such as Social Security, healthcare, and education services.

2. Financial and administrative burdens: This imposes significant costs on states, as they must absorb the costs of providing essential services without federal funding.

3. Creating a multi-generational underclass: Risking the creation of a class of individuals without legal status in the U.S.

Legal Arguments.

The plaintiffs rely on a range of legal arguments, including:

Constitutional Provisions

1. Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause: Guarantees citizenship to all individuals born in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction.

2. Equal Protection Clause: Prohibits states from denying anyone equal protection under the law, which includes access to citizenship.

Precedents and Legal Interpretations

1. United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898): The Supreme Court ruled that a child born in the U.S. to non-citizen parents is entitled to citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment.

2. Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857): The Citizenship Clause was adopted to overturn Dred Scott, ensuring birthright citizenship regardless of race or parentage.

Federal Statutory Law

1. Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), 8 U.S.C. § 1401(a): Codifies the Citizenship Clause, confirming that individuals born in the U.S. and subject to its jurisdiction are U.S. citizens at birth.

2. Medicaid and CHIP Laws: Federal statutes require states to provide healthcare coverage for qualifying children based on citizenship or lawful immigration status.

Federal Case Law on Equal Protection and Benefits.

1. Plyler v. Doe (1982): States cannot deny undocumented children access to public education.

Specific Legal Violations

The plaintiffs argue that the executive order:

1. Violates the Fourteenth Amendment: Denies birthright citizenship without constitutional authority.

2. Violates the Administrative Procedure Act (APA): The executive order is arbitrary, capricious, and contrary to law under the APA.

3. Causes Financial and Administrative Harm to States: Stripping children of citizenship deprives states of federal reimbursements tied to citizenship.

Changing Birthright Citizenship Through Law.

To change the concept of birthright citizenship, Congress would need to pass a constitutional amendment or legislation that revises the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This could involve:

1. Proposing a Constitutional Amendment: A two-thirds majority in both the House and Senate or a national convention called by two-thirds of the state legislatures would be required.

2. Passing Legislation: Congress could pass a bill revising the Citizenship Clause, but this would likely face significant legal challenges.

In Conclusion, the debate over birthright citizenship in the United States is complex and contentious. While some argue that it is a fundamental right guaranteed by the 14th Amendment, others claim that it is being abused by individuals seeking to exploit the system. As the legal challenges to President Trump’s executive order continue to unfold, the future of birthright citizenship hangs in the balance.

Ultimately, any changes to the concept of birthright citizenship will require careful consideration of the constitutional, legal, and humanitarian implications. Policymakers and stakeholders must engage in a nuanced and informed discussion about the issue, considering the diverse perspectives and experiences of individuals and communities affected by this fundamental aspect of American law.

As the nation grapples with the complexities of immigration policy and the meaning of citizenship, it is essential to remember that the principles of equality, justice, and compassion enshrined in the Constitution must guide our decision-making. The future of birthright citizenship is not just a legal or political issue – it is a matter of fundamental human rights and dignity.